Fear not, citizens of Rancho Cucamonga. That paunchy, 61-year-old man you might have seen over the winter, throwing a baseball over and over against the exterior walls of various empty warehouses in your Southern California town—he means no harm. He is Mike Ashman, perfectly innocuous and gainfully employed by the Angels for a skill in which he takes great pride. Ashman is a professional batting practice pitcher. That is, he takes the field two hours before each Angels game to throw 60-mph strikes to Mike Trout and the rest of the lineup, to help them find their groove.

It’s all he does, but as narrow as his job description is, Ashman can’t just show up at spring training and throw 500 pitches a day, every day for nine months straight. He must build toward that workload. So there he is each winter, pelting those poor buildings with “fastballs” every five seconds, replacing the ball every few days once it disintegrates, until he can throw for 20 minutes straight. Only then will he be ready for the gantlet ahead.

Ashman isn’t alone. Last season nine MLB teams employed a full-time batting practice pitcher. The other 21 teams relied on a combination of bullpen catchers, coaches and ancillary staffers to fill the role. Whoever does it must first pass the critical test of earning the players’ approval, for the only thing that can annoy a hitter quicker than presenting him with an erratic practice arm would be canceling BP altogether, in which case you might as well take his protective cup, too.

Even Trout needs a bit of positive affirmation before stepping in to face, say, the hissing comets of Lucas Giolito, against whom he is statistically likely to fail, anyway. As Ted Williams—himself an occasional BP pitcher during his playing days—famously wrote in The Science of Hitting, striking a baseball with a bat “is the single most difficult thing to do in sport.” Batting practice, then, is like therapy, a wordless, two-person conversation intended to build the confidence of the man about to enter the arena. Which makes Ashman a kind of psychoanalyst. “The main thing is to just be available to them,” says Ashman, who played six minor league seasons as a corner infielder in the 1980s. He’s talking about throwing, not counseling, although a steady stream of hittable pitches provides that, too. “I tell our new players, I’m always here. You’ll never have to go looking for me. It’s the reason I’ve lasted 21 years.”

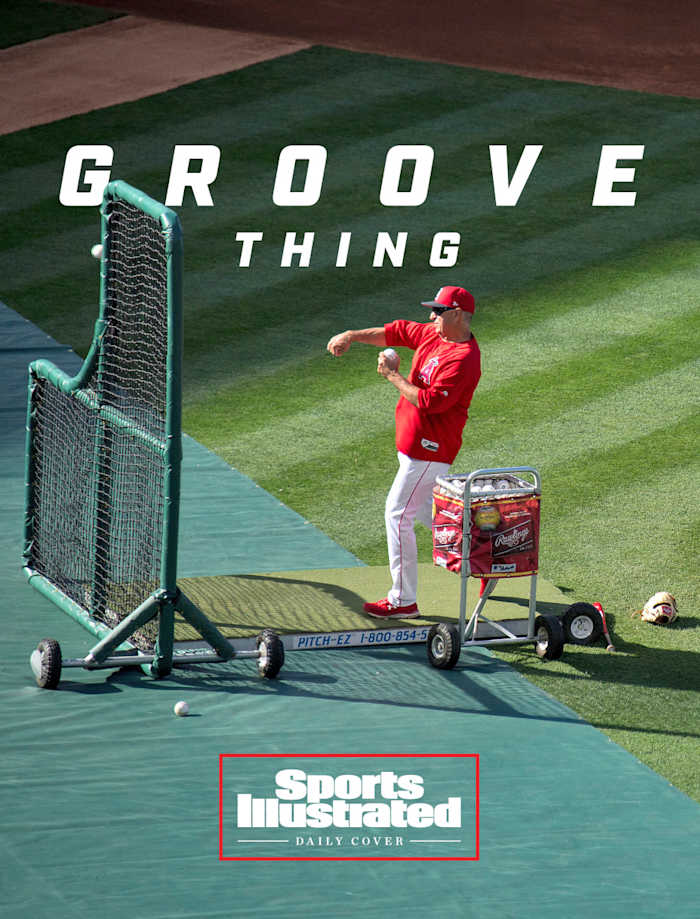

That, and his gift for doing what rostered pitchers try to avoid. “My job is to get lit up,” says 54-year-old Dino Ebel, the Dodgers’ main BP pitcher. “The main goal is to have each guy feel like he’s the best hitter in the world when they leave the cage.”

Ebel, who also coaches third base for the reigning world champs, throws to Group 1 before each game. Every team organizes BP the same way, with Group 1 consisting of the team’s top three or four hitters, and the coaching staff’s most reliable arm serving as a sort of staff ace. The rest of the Dodgers’ rotation of BP hurlers is filled out by special assistant José Vizcaíno, who throws to Group 2, and bullpen catcher Steve Cilladi, who throws to Group 3. Other staffers, including game-planning coach Danny Lehmann, fill in like spot starters.

Ashman is a 21st-century Old Hoss Radbourn, throwing all day, every day, to just about every player. He travels with the Angels, and usually arrives at the ballpark at 1 p.m. (for a 7 p.m. game) to hit the lights in the indoor batting cage and check the all-important L-screen, the movable, netted barrier between him and the hitter. By that time, an Angels batsman or two has usually strolled in for early work.

“Since I was a kid, I’ve only needed a throw or two to get loose,” says Ashman. So off he goes, placing three balls in his left hand and one in his right, firing from the latter every five seconds, from 50 feet away instead of 60 to create the illusion of big league velocity. Returning to the basket for four more balls, repeating for 20 minutes or so.

Forget pitch counts or precautionary shutdowns, Ashman throws at least 500 pitches a day, with a goal of just five sailing outside the strike zone. His performance reviews happen in real time, each thwack of wood on rawhide representing a thumbs-up from his higher-paid coworker. Over the course of a season, he takes only two or three days off. He throws by himself on travel days—once he finds a good wall—and on other days when there isn’t a game, because “if I don’t throw for two days in a row, I struggle to find it again.”

A productive BP session can resemble a ballet, the give and take conjuring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland performing The Nutcracker—except the accompaniment is Drake or merengue instead of Tchaikovsky, and there is significantly more spitting.

A good BP pitcher learns where every hitter on the roster likes the ball. Then he puts it there. And nine times out of 10 won’t do. If “throw strikes” is the cardinal rule for real pitchers, it’s the papal rule for BP hurlers, who must possess Greg Maddux–level marksmanship above all else. Balls thrown outside a Group 1 hitter’s sweet spot can earn you a glance of mild annoyance, or the ol’ step-out-of-the-box-lean-back-and-reset move (those sting) or an impatient query about whether you’re all right. Too many will get you a clap on the shoulder and a somber, two-person stroll on the outfield grass that ends with “Best of luck.”

BP pitchers need to know which hitters like to see a cutter from time to time. (Ashman can still unleash a filthy one when the planets line up just right.) When new players arrive, he must get to know their wheelhouses like his own home. Ashman recalls that when the Angels added Anthony Rendon to the roster in ’20, the All-Star slugger “let me know I was throwing middle-in too much, so I made that adjustment.”

Quick reflexes are a plus. Screamers with triple-digit exit velocity will rip through L-screens and hunt down ankles and elbows that stray outside their metal frames. In 1999 Ed Sedar, a longtime coach and the principal BP arm for the Brewers, welcomed former All-Star pitcher Bill (Soup) Campbell to the staff and took him up on his offer to throw BP. The ensuing CRACK-hiss-thump that terminated at Campbell’s ribs prompted a stroll to the mound. “You know you gotta finish,” Sedar whispered to his doubled-over colleague. “You can’t let them know it hurt.”

“I know,” Campbell rasped between whimpers.

The record shows that was Soup’s only season as a coach.

The pregame session on the field is where the spotlight shines brightest on Sedar, Ashman and their brothers in arms. (Sisters, too. Alyssa Nakken of the Giants and Justine Siegal, who has thrown for multiple clubs, toss excellent BP.) Working from a turf mat placed in front of the mound to protect the sacred dirt beneath, and before an audience of unoccupied seats, big league ballplayers and chatting executives, the setting isn’t for the timid. Big league stadiums can be intimidating places, even when empty. Adding to the pressure: In recent years most team-affiliated networks have started televising batting practice.

“We needed a lefty one year,” Ashman says, “so a guy I played with in college, I knew he threw BP at his high school—I invited him in.” His buddy threw well in the subterranean cage, so a senior Angels coach told him to come back before the game. Ashman, unconvinced, wanted him to mimic what he’d just done but on the field. “He was so nervous he couldn’t throw a strike. He said, ‘I didn’t think it would be this tough.’

“We had another guy. He started off good, but then he tailed off. He came up to me one day and said, ‘Hey, [infielder] Howie [Kendrick] said I threw good today!’ ” Ashman knew it was over. “I told him, ‘You can be bad once in a while. But you can’t be good once in a while.”

Ebel has a simple description of his task: "My job is to get lit up."

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

Laypersons need not apply, says Dodgers third baseman Justin Turner, a mainstay of Ebel’s group: “It’s hard. If you go to a park and watch an average fan with a buddy playing catch, they’re all over the place. Now think about standing 40 feet from guys and having to throw it over a 17-inch plate, and throw strikes over and over. It’s definitely a skill that we appreciate.”

Says Ashman, “You have to be mentally tough to do it the first time, then you have to become even more mentally tough because they give you crap all the time. Trout and those guys like to get on me about the way I’m throwing. I know they’re joking, trying to get under my skin, but you take it serious! Like, Wow, was I bad today?”

Then there’s the wear and tear. The 59-year-old Sedar has thrown to hitters in the Brewers’ organization for 30 years and has the medical records to prove it. “I’ve had rotator cuff surgery, [a] sore elbow. . . . I’ve been hit in my pitching hand [with a line drive] and had to tape my fingers together because I knew I still had to throw,” he says. “I mean, you’re counted on.”

Skipping a start isn’t an option, especially with the big league club, which Sedar has served as a base coach and Group 1 BP arm since ’07. “You know how superstitious major league players are,” he says, laughing. “They have their routines.” During a baserunning drill a few spring trainings ago, some young buck crumpled Sedar’s leg with an aggressive slide, which led to knee replacement surgery in the fall—after he’d winced through months of BP sessions.

His throwing shoulder gave way in the spring of 2001 while he was teaching his rookie-ball Ogden (Utah) Raptors how to dive back to first. He still threw BP every day, albeit with a funky new delivery. Future big leaguers Corey Hart and J.J. Hardy were on that team. “Every time I see them they laugh about the season we had to turn the L-screen around so I could throw sidearm,” Sedar says. The new setup exposed his right foot, which absorbed a half dozen line drives that year. But it all paid off in the playoffs against Idaho Falls, Sedar adds proudly, when his team roughed up a sidewinding closer who threw like its gimpy manager.

Cilladi, the Dodgers’ buff, 34-year-old bullpen catcher, prepares himself for these rigors like a Navy SEAL. Typically he’s the first man in the Dodger Stadium weight room each morning. His main mission is to stave off the shoulder and elbow breakdowns that every BP pitcher encounters around August.

Cilladi’s primary job is to sink into a crouch and provide a willing mitt to any pitcher in need of one, but during his seven years with the Dodgers he has become a jack-of-all-trades who even helps sort scouting data. By the time Cilladi takes the mat to deliver BP, his glove hand has already absorbed a few hundred throws. Some are of the standing long-toss variety; others are 98-mph mortar shells from Brusdar Graterol.

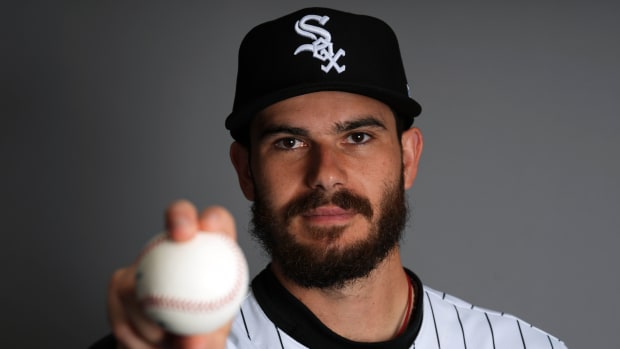

Cilladi can still feel the fastball thrown to him last year by Dylan Floro (now with the Marlins), which collided with his gloved thumb in a way that made Cilladi emit a sound like a wounded kitten. Cilladi, a 33rd-round draft pick in 2009 who played five years in the minors, had never asked for a day off, at any job. The Dodgers gave him two. “I know everyone here cares about me,” he says, “but it’s important that the [pitchers] never even think about whether I’m hurt.” Then he repeats the line that is every bullpen catcher and BP pitcher’s mantra: “This is a service job.”

Which is why, when Ashman felt a twinge in his elbow in 2014, he clenched his jaw and kept throwing, despite the MRI that revealed a torn flexor tendon. He received a daily Toradol shot during the Halos’ ALDS loss to the Royals, which was followed by offseason surgery on the Angels’ most important arm that isn’t represented by an agent.

During games, Ashman can be found by the cage under the stands, waiting for that night’s DH to pop in. Shohei Ohtani shows up like clockwork between his at bats. Albert Pujols prefers to see “flips” between plate appearances. For that, Ashman slides his trusty L-screen forward, until it’s about 10 feet from Pujols, then sits behind it and tosses balls into the future Hall of Famer’s wheelhouse, like he’s playing darts, the rhythmic flip-thwack, flip-thwack, flip-thwack of their work punctuated by the occasional ping! of a liner finding the L-screen’s frame.

Since Pujols’s arrival in 2012, Ashman has heard the crowd respond to a home run off Pujols’s bat following one of their flip sessions 163 times. But there’s no time to celebrate in the cellar. “Sometimes a position player like Trout or [Justin] Upton will run down and say, ‘Ash, gimme some curveballs!’ You have to stay ready.”

When Ashman was younger, and his arm livelier, he used to play a game, around the fifth inning, with guys who weren’t in the lineup. He’d pitch from 40 feet away and throw everything in his meager arsenal, changing speeds, spins and locations to try to strike them out. The idea being: “Throwing 60 mph from 40 feet away probably looks like 95 from 60 feet.” Score was kept. Home runs admired. Arguments were frequent. “[Former Angel] Garret Anderson loved it. He said it kept him sharp.”

Sadly, Ashman’s days as Bob Gibson of the Basement are over. “Physically, I can’t do it anymore,” he says, chuckling. But he can get it over when it counts, to the tune of 135,000 pitches per year.

Williams wasn't above throwing BP in the days before the L-screen.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library/Leslie Jones Collection

As critical as it is in today’s game, batting practice was hardly a consideration during the sport’s infancy. In his book Game of Inches, Peter Morris, historian for the Society of American Baseball Research, informs us that BP was a rarity before 1900. Baseballs were expensive, for one thing, and knocking them around the park and retrieving them was tiring and time-consuming. (The geniuses of the Industrial Revolution had yet to invent the batting cage.) But the main reason BP was eschewed was, according to Morris, “hitting was viewed as an instinctive skill that could not be learned or taught.” (Contemporary hitters often whisper some version of this line while watching pitchers attempt BP.)

Harry Wright is most often credited with the advent of pregame cuts when he was managing in Philadelphia in the 1880s. Henry Chadwick, one of the game’s founding fathers, witnessed Wright encouraging his team “to bat at a dozen balls each pitched to them for hitting purpose.” The first batting practice pitcher appears to have materialized in Detroit in 1886, in the form of a washed-up southpaw named Howard Lawrence, whom The Boston Globe reported “may develop into a valuable man in time.”

By 1907, Detroit manager Hugh Jennings had streamlined the process, according to The Detroit News: “It’s like standing in line at a barber shop. ‘You’re next!’ cries Jennings, and each man tries to put one over the fence.”

Which brings us to the modern batting practice pitcher’s only moment in the sun. (Figuratively speaking, of course, because farmers’ tans are as ubiquitous among BP pitchers as scrubs are to surgeons.)

Ebel helped Vladimir Guerrero Sr. win the 2007 Home Run Derby, then pitched to Pujols in ’15. In ’19 he helped Joc Pederson set the record for most career homers in Derby history. (That was Cilladi you didn’t notice squatting behind Bryce Harper when Harper clouted 19 final-round bombs off his dad to win the ’18 crown. “I’ll never forget it,” Cilladi says. “Best seat in the house.”)

The Yankees’ full-time batting practice pitcher, Danilo Valiente, helped Aaron Judge slug 47 homers in just 76 swings to take the 2017 Derby—after which Valiente leapt into Judge’s arms like a kid, the culmination of a remarkable journey. A former coach in Havana who earned the equivalent of $7.50 a month, Valiente came to the U.S. in 2006, weeks before his wife, Isabel, died of cancer. “Heartbroken, Valiente sought refuge in baseball,” The New York Times reported in 2014.

Valiente tracked down and intercepted Mark Newman, the Yankees’ senior VP for baseball operations, during one of the executive’s morning walks near the team’s minor league complex in Tampa. A conversation followed, then an invitation to the ballpark. An L-screen appeared. Valiente threw all strikes. Nearly as important, the players fell in love with his jocular cage-side manner. The Yankees made him their full-time BP hurler in 2014. Derek Jeter insisted that Valiente be introduced by name to the Yankee Stadium crowd of 48,142 on Opening Day, a moment that moved Valiente to tears.

Cut to 2017 and the gap-toothed Goliath whose BP moonshots sailed over the restaurant in SkyDome, smashed a TV in the Yankee Stadium terrace and went viral online. Those balls were delivered to Judge by Valiente, using a nondeceptive, over-the-top motion passed down to him long ago by a hitting coach named Rolando (Chavito) Nunez. “Even the days I don’t feel good in the cages,” Judge said that summer, “he somehow finds a way to make me feel good during BP.”

With help from Valiente, Judge blasted 47 homers at the 2017 Home Run Derby.

Alex Trautwig/MLB/Getty Images

Pitching machines are gradually creeping in, though, changing this little corner of the game the way analytics, the infield shift and the three-hitter rule have altered what happens in competition. “But there’s no replacing the value of seeing a ball roll off a [BP] pitcher’s fingers,” says Sedar, the battered Brewers coach who, mercifully, has been moved to an off-field, advisory role with Milwaukee this year. Hitters’ timing relies on the sight of a person stepping and delivering in their direction. But it’s 2021 now; there are rovers on Mars, and pitching machines are becoming more human all the time.

“And they can throw with more velocity,” Sedar adds.

“And all these different spins,” says Ashman.

It will be more difficult to replace the camaraderie and the well-timed insult or Attaboy! that can help ward off slumps hiding just around the corner. No robot can supplant Ebel’s “four-seam fastballs as straight as you can send ’em, so you can make ’em feel good.” Much less his raspy laugh.

As any good bullpen catcher or BP pitcher knows, a big part of the job is staying behind the scenes, the way Cilladi did when he sneaked into a corner of the Dodgers’ bullpen to remove his shin guards just before Julio Urias delivered the final pitch of the 2020 World Series. “In my role,” he says, “you do not want to be the guy caught on TV, acting like it’s over before the final out.”

When that final out arrived, the Dodger who had caught Urias more than anyone else on the payroll watched the distinction between players and other uniformed team members vanish. In that instant, “everyone became a kid.”

Ashman, asked to provide his proudest moment, doesn’t hesitate. “Every day,” he says, his voice rising with adolescent excitement. “I get to throw to major league hitters.”

More Baseball Coverage:

• 'Heroes of the People': Yankees Fans Taunt Astros for First Time Since Scandal

• Inside Kris Bryant's Early-Season Resurgence

• Remembering Pitchers at the Plate

• The Myth of Shohei Ohtani is Proving Real Again